The Death of Catholic England

The Voices of Morebath: Reformation and Rebellion in an English Village

By Eamon Duffy

Publisher: Yale University Press

Pages: 232

Price: $21.95

Review Author: William J. Tighe

In 1992 Eamon Duffy, a Fellow of Magdalen College, Cambridge, and a Reader in Church History in the Divinity Faculty of Cambridge University, published a monumental book of 654 pages titled The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England c.1400-c.1580 (also by Yale University Press). This book analyzed in great detail the Catholicism of pre-Reformation England, and then described how it was destroyed in gradual stages by successive Tudor monarchs from roughly 1535 onward. It also described the successful effort to restore Catholicism during the five-year reign of Mary Tudor (1553-1558), an effort cut short by the queen’s death and the succession of her Protestant half-sister, Elizabeth, whose long reign (1558-1603) ensured the success of the ambiguously Protestant English Reformation. The book became something of a bestseller in England, unexpectedly so because it is nothing less than a full-scale assault on the Protestant Myth of the English Reformation. That Myth holds that the Reformation, however arbitrarily introduced to satisfy the whims of Henry VIII and Elizabeth, and however much accompanied by plunder and spoliation, was a “progressive” movement toward “spiritual and national maturity and self-reliance” and, as such, after the initial shocks, was welcomed with eagerness or at least acquiescence by the vast majority of Englishmen — a myth that was a constituent part of the “Whig Interpretation of History” that viewed the Reformation as the inception of England’s rise to greatness with Protestantism (religious or secularized) as a fundamental trait of the “English character.” However, as Duffy claimed, basing his views in part on surviving churchwardens’ accounts indicating how widespread was the refusal to surrender the condemned apparatus of Catholic worship throughout England until well into Elizabeth’s reign, the Reformation was received by the great mass of Englishmen with reluctance, resentment, and resistance. Catholic England did not “pass away”; it was murdered.

Since the early 1970s there has been a movement of “revisionism” among scholars of the English Reformation that had been making an impact in the historical profession, but not without attracting resistance and contradiction from English nationalistic and Protestant scholars. However, the movement had not made any impression to speak of among the reading public. But with Duffy’s book, revisionism “arrived” in an unmistakable way. True, there were (and are) some attempts in uninformed English Protestant circles to wave aside the book’s conclusions as “apologetic Catholic historiography,” since Duffy is known as a practicing Catholic. One of the first revisionist books, J.J. Scarisbrick’s The Reformation and the English People, had had as its author an English Catholic academic who had attracted media attention, as well as obloquy and contempt from many of his fellow academics, in his capacity as long-term head of the English prolife organization LIFE. But a flood of revisionist publications in the 1990s authored by scholars of all religious professions or none has abated such captious and obscurantist criticism. Now, in The Voices of Morebath, Duffy has produced a detailed account of a rural Devonshire parish church during the 54-year incumbency (1520-1574) of its Vicar (parish priest), Christopher Trychay (the name rhymes with “Dickey”), which shows how the developments which Duffy discussed in a broader and wider-ranging fashion in his earlier work impacted on one particular place, its people, church, and priest.

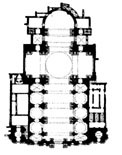

Morebath is a remote district in north Devon, the population of which stood at about 150 around 1550. Today it is still (relatively) remote and sparsely populated, and the medieval parish church has little of historic interest in it. Its claim to historical fame stems from the extraordinarily detailed Churchwardens’ Accounts that Sir Christopher (“Sir” was the common medieval English honorific title for a priest who was not a university graduate) kept throughout his time at Morebath, which have survived from 1527 onwards. Born in the Devon village of Culmstock probably in the early 1490s, Christopher Trychay was ordained in 1515, arrived in Morebath as its Vicar in August 1520, and was buried in the church there (St. George) on May 27, 1574.

Churchwardens’ Accounts from 16th-century England are no rarity, but the Morebath Accounts contain extraordinary detail and were clearly written down by the priest, even when they are presented in the names of the wardens of the various “stores,” or funds, which played an important role in the administration and devotional life of the parish, and were read aloud by him at general meetings of the parishioners, usually in the church after Mass on Sunday several times a year. These extraordinary accounts, with their itemizations of expenditures, bequests, and funds set apart for long-term projects, indicate how, in both 1549 under Edward and in 1559 under Elizabeth, some of the most precious and necessary Catholic paraphernalia such as the Missal and many of the vestments had been given into the hands of parishioners for safekeeping rather than being surrendered to the authorities for destruction. The priest’s occasional asides reveal his dismay at the religious changes of Edward VI’s reign and his joy at Queen Mary’s restoration of Catholicism, and his praise of those who returned to the church religious items which they had purloined or bought to save them from destruction in King Edward’s time — “lyke tru and faythefull crystyn pepyll this was restoreyd to this churche by the wyche doyngis hyt schowyth that they dyd lyke good catholyke men.” Most extraordinary of all, the accounts reveal — and Duffy tells us how long it took him to accept that this was the true meaning of these laconic and partly effaced entries — that the parish raised funds to equip five young men of the parish to send them off to fight against the Crown in the “Prayer Book Rebellion” of June through August 1549, when the people of Devon and Cornwall rose in revolt in protest against the abolition by the Act of Parliament of the immemorial Catholic Latin services and their replacement by the 1549 Book of Common Prayer. The rebels were defeated in a pitched battle on August 5. Over 3,000 sons of Devon and Cornwall lost their lives in the battle and in the slaughter that followed, and only two of the five young men sent out from Morebath ever returned. The accounts also reveal how the aging Sir Christopher accommodated himself, if without any deep change of heart, to the return of the Reformation under Elizabeth.

The book is divided into seven chapters, of which the first four introduce the place, the church accounts, and Sir Christopher, and then discuss the social and economic life of the parish community and, finally, its religious life, focusing particularly upon the energy and zeal with which Sir Christopher set about enlivening the piety of the parish in the years after his arrival as Vicar. In particular Sir Christopher introduced and successfully propagated a devotion to St. Sidwell, Exeter’s local saint, a young maiden whose piety had so annoyed her stepmother in Anglo-Saxon times some 800 years previously that the latter had procured her murder by some of the laborers on her farm. By the late 1520s small donations, including bequests of sheep, had enabled a “store” to be set up to maintain candles burning around the side-altar in the north aisle of the church, to erect an “image,” or statue, of St. Sidwell alongside the “Salvator Mundi” image of Christ above that altar.

Duffy discusses what we can and cannot know about the religious attitudes of these “stolid, weather-beaten moorland farmers and their wives,” opining that “their Christianity, in all likelihood, was largely conventional, which is not to say that it was either insincere or superficial.” They were “people for whom Christianity is about living right and dying well, but also about belonging, both to a place and to a lineage, about winning respectability, ensuring safe child-birth, about the best time to prune apples and the most effective way to ease sciatica or stop a diarrohea.” The final three chapters recount and analyze the destruction of all of what Sir Christopher had labored to promote and that the folk of Morebath held dear.

Despite the break with Rome, the suppression of the monasteries in the 1530s, and the armed protest against these changes in northern England known as the Pilgrimage of Grace in 1536, life continued as before in Morebath and elsewhere until September 1538, when the Crown decreed the abolition of the “superstitious” burning of lights (candles) before images, save before the reserved Sacrament and the great Crucifix (the “Rood” or “Holy Rood”) in the Roodloft. This was a blow to the exuberance of Morebath’s devotional life. The various “stores” had to be reorganized and consolidated, but various projects such as the rebuilding of the Church House — the building in which feasts and communal occasions were held — and repairing and refurbishing the church itself continued, attracted donations, right to the end of Henry VIII’s reign in 1547. Then the roof fell in, as in July 1547 those who governed England in the name of the boy-king Edward VI, soon to become himself a precociously fanatical Protestant, decreed the abolition of all lights and candles in churches (except for one on the High Altar), forbade all processions (elaborate processions before Mass were a characteristic feature of the medieval variants of the Roman Rite in use in England before the Reformation), and mandated that all images whatsoever were to be removed from churches and destroyed. In Morebath most of the “stores” were wound up, the church sheep and church bees (which provided wax for the candles and honey for the priest) sold off (Sir Christopher himself bought the bees), and the organizations that maintained them successively disbanded. In 1549 came the liturgical changes that led to the Prayer Book Rebellion, and the rebellion was followed by the confiscation of the church bells (which the parish had to buy back at its own expense), the destruction of the Roodloft, and the burning of its great Crucifix and related imagery, as well as St. Sidwell’s statue and the other images. In 1551 the altars had to go, being replaced by a wooden Communion Table, and there were further confiscations in 1553.

Word of Catholic Mary’s succession to the throne reached Exeter when the much-disliked new Protestant bishop, Matthew Coverdale, was preaching to the citizens in Exeter Cathedral, and as the whispered report that Mary was now queen went through the assembly, most of those present stood up and walked out, leaving Coverdale to address a handful of his followers. Mary’s reign saw a tremendous, sustained, and successful effort to restore the fullness of Catholic faith and worship to Morebath, as elsewhere, and most of the “stores” that had disappeared at Morebath from 1538 onward were revived. After 1559, and the reimposition of Protestant worship in that year, it all disappeared again, and once again Sir Christopher arranged for the Missal and many of the Catholic vestments to be hidden away against the arrival of a better day — which never came. Slowly the new interior arrangements of the church acquired an appearance of greater permanence, as the interior was refurnished in 1568, an old silken Catholic vestment turned into a covering for the Communion Table in 1570, the church’s chalice was confiscated in 1571 (although instead of buying a Protestant communion cup with the funds paid to the church in recompense for the confiscation, which was the purpose of the requirement, Sir Christopher made use of another old chalice which had been concealed previously), and various defenses of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, such as John Jewel’s Apology and the Thirty-Nine Articles (whose purchase and installation in churches the Crown now required) were acquired between 1571 and 1573. When he died in May 1574, Sir Christopher was buried in the chancel, as he had asked, above the Communion Table, probably on the site where the High Altar had stood. His burial fee was employed subsequently toward the cost of obtaining a Protestant communion cup for the church a year after his decease.

Sir Christopher might be taken for a Reformation-era version of the Vicar of Bray, that proverbial and mythological Anglican parson who kept his position and shifted his views through all the changes of politics and kings between Charles II’s Restoration in 1660 and the advent of George I and the House of Hanover in 1714 (the refrain to the verses of the 18th-century drinking song “The Vicar of Bray,” runs, “And this is the Law, I will maintain/ Unto my Dying Day, Sir!/ That whatsoever King shall Reign/ I’ll be the Vicar of Bray, Sir!”). But Duffy denies that Sir Christopher was like the Vicar of Bray, in both The Stripping of the Altars and the present book.

In the former he wrote: “Christopher Trychay…conformed and conformed again, but he was no vicar of Bray. Reading his church book it is hard to see what else such a man in such a time and place could have done. For him, religion was, above all, local and particular, ‘rooted in one dear perpetual place,’ his piety centered on this parish, this church, these people. It was not a matter of mere fear, though going with his wardens to be quizzed for the commissioners for church goods in Exeter he would have seen the rows of rebel heads above the gates, and registered the fate of those who resisted the Crown. Some priests had led their people against the new religion, and had been hanged in their chasubles for their pains, and still the altars had come down, the royal arms replaced the Rood, the beloved images had been axed and burned. Some priests, probably more than we are likely to be able to count, refused to serve the new order, and moved away — to secular life, to a diminished role as a schoolmaster or a chaplain in a traditionalist and ultimately recusant household, to exile abroad. But for a man like Trychay there was nowhere to be except with the people he had baptized, shriven, married and buried for two generations…. It was not for them to rule the winds: the conscience of the prince was in the hands of God, and the people must make shift to do as best they could under the prince.”

And in the present book he writes: “Church accounts are not the place to look for strong doctrinal convictions, but it is perhaps significant that Sir Christopher’s sternest condemnation of the Edwardine experiment was not that it has been born in schism and ended in heresy, but that under it Morebath church and its contents had ‘ever decayed.’ His traditionalism must of course have had a doctrinal content, of the kind spelled out in the rebel demands of 1549 — loyalty to the Mass, the ancient faith, the sacraments — but it was before everything else informed by the genius of place; his religion in the end was the religion of Morebath. The strength and the weakness of such a religion were the same — the local character of its conservatism, the binding of its practitioners to a place, whatever change befell. Not for priests like Sir Christopher the walk away from the protecting known into the wilderness, undertaken by Protestant separatist and Catholic recusant alike, men and women in pursuit of principle at the cost of the dear and familiar. The unthinkable alternative to conformity was to leave his vicarage and the people he had baptized, married and buried for forty years. It was a course few took, for in 1559 there must have seemed very little he or anyone else could do if the Queen chose to stay out of the Pope’s communion, even supposing the Pope figured very much at any time on Morebath’s horizon.”

Recently I received a letter from an English Catholic friend in which he commented that while The Voices of Morebath was not so melancholic a book for him as The Stripping of the Altars had been, it was, given the “bitter ironies” in which the book abounds, even more poignant. He ended his letter: “One does marvel at the speed with which people seem to have accepted change, but is this any different from the way in which most of our Catholic contemporaries have seen nothing to regret in the priest suddenly turning to face them whilst addressing God in a banal vernacular?” Buy this book, read it, and allow yourself to become acquainted with a small corner of the vanished world of Catholic England.

You May Also Enjoy

The Vicar reminded us that the Anglican Communion embraces a wide variety of lifestyles and said the time had come for him to come out of the closet.

The wealthy Anglican Churches promote a radical transformation of Christianity to make it over in a way agreeable to elite society.

A review of Anglican Difficulties